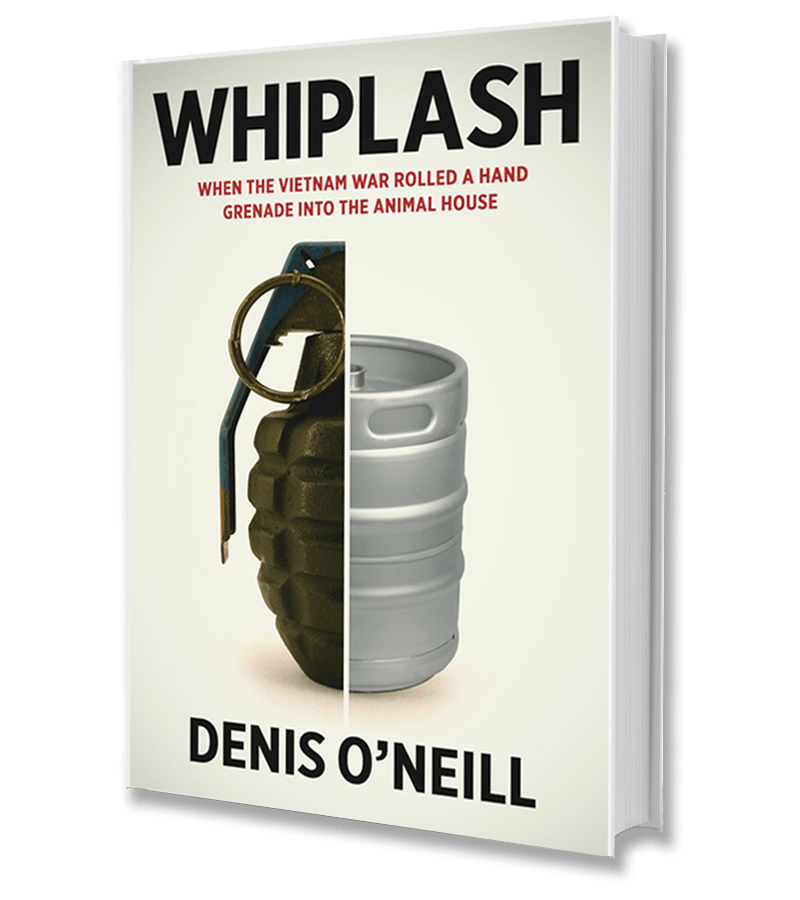

Denis R. O'neill

Author, Screenwriter & Producer

Whiplash: Author’s Letter

At some point in your life – a moment as profound to you as it is statistically unremarkable – you realize that a lot more of your life is in the rear-view mirror than out the front windshield. The awareness of that growing imbalance had been festering in me for some time. I suppose 60th birthdays have a way of bringing focus to the passage of time. But there’s nothing like a 40th college reunion to really bring home the autumn-of-your-life bacon. Especially when your graduation year was 1970.

Memory being memory – sieve-like, selective and often prone to wistful, or heroic embellishment – it was good to reconvene with a tent full of fellow Boomers and attempt to piece together a reasonable version of the story from a distance of four decades – ages hence in Robert Frost’s provocative phrase – with the assistance of the same kind of keg beer that fueled many of those episodes all those years ago… at the very location where they all took place – like a jury visiting the scene of the crime.

Baker Library

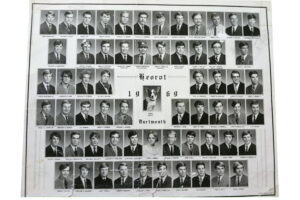

The place, then, as now, was Hanover, New Hampshire. The college was Dartmouth, an entity with which I feel a particular kinship given a shared December 13th birthday. And the handle “fellow Boomers” is gender correct as this was a time when Dartmouth was an all male institution – as it had been for the two hundred years leading up to the time of this story. There were actually seven women who arrived on campus in the fall of 1968 to take part in an experimental, yearlong theater program. Three thousand men and seven intrepid women who naturally came to be known as the “Magnificent Seven”.

They were just one of the elements that stirred the student body in those days. These were remarkable times on and off campus – a period of trauma and turmoil maybe never before experienced by a generation of college undergraduates, certainly not since.

By way of historic compression: if you started in the winter and early spring of 1968, when Eugene McCarthy – campaigning in Hanover and throughout New Hampshire – upset incumbent Lyndon Johnson in the New Hampshire primary leading to Johnson’s withdrawal from the Presidential race… and marched through the assassinations of Martin Luther King, Jr. in April, then Robert F. Kennedy in June… you landed in Chicago later that summer at the Democratic National Convention, where Hubert Humphrey prevailed in a flurry of tear gas, then lost the general election in November to Richard Nixon.

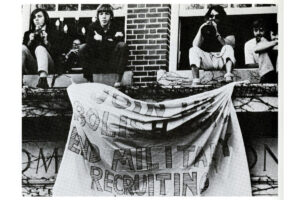

In the winter of the following year, the secret bombing of Cambodia began, student protests on college campuses grew in leaps and bounds, and some schools like Dartmouth endured spring takeovers of administration buildings by SDS members and other anti-war protesters… leading to the defining cultural event of the era, in August of 1969, the Woodstock Music Festival.

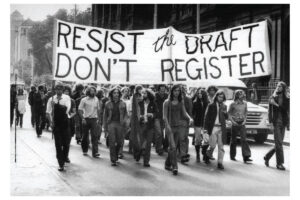

In dramatic counterpoint, the summer of love was followed by a season of anger and anxiety. Campuses already tense from protests were further inflamed at the end of that fall semester when the military draft lottery was re-instituted, and on December 1st every eligible college student found out by luck of a drawn blue capsule whether he was going to be drafted to go fight in a war in Southeast Asia, be spared by dint of an accident of birth, or find himself in numerical no-man’s land (the eligible single male body count in his home district determining if a mid-range number like mine – 163 – would mean draft or deferment). Canada entered the radar for the first time, as the notion of being a conscientious objector crept into many a master plan.

Vietnam Draft Backlash

The country was on an anti-war boil: it boiled over on the campus of Kent State on May 4th when students protesting the escalating bombing of Cambodia were fired upon by National Guardsmen, killing four students. At Dartmouth, in the anxious aftermath, further upheaval was avoided when the administration gave students the chance of accepting a pass/fail for the remainder of the term – basically the month of May. It was a way of lowering campus fever. A year earlier, the administration building had been taken over by angry students. Hours later, in the middle of that night, baton wielding state troopers – with a green light from the college – reclaimed the building, dragging students into buses and into jail (some for 30 day sentences). Now, in the spring of 1970, with another year of agitation piled onto the implementation of the draft lottery, the same building might have burned to the ground if the college had attempted business as usual.

Coincidentally, the weather that May was the most glorious stretch of warm days and blue skies anyone could remember in New England at that time of year. It was like a giant time out in the midst of a national uprising – for seniors, a month of sunbathing and beer drinking and road trips and reflection before they became the first class since WWII to graduate with diplomas and draft numbers.

I mention these events in one breath because from the winter of 1968 until June of 1970 – when we graduated – it seemed like the semesters crashed together in a giant scrum of set pieces that would be right at home in a Jerry Bruckheimer movie. When unexpected history and reliably chronological (collegiate) hormones collide, it makes for momentous times.

In my memory those years – junior and senior – seem of a kind. And so I’ve taken the liberty of blending them into one year, 1969-1970, in order to reflect the intensity of what it felt like to live through them. Whiplash was the order of the day, with “Animal House” road trips, fraternity shenanigans and other collegiate misadventures co-existing with life changing national and world events in an almost surreal, black comedy. If they weren’t precisely the best of times, the worst of times, they were, if nothing else, the most memorable of times (not to mention a tale of two campuses after December 1, 1969).

One of the most indelible characters of those memorable times was one of the “Magnificent Seven” – a junior year transfer student who was not only one of the first women to attend Dartmouth, but the first woman to pledge a fraternity – Heorot House – which happened to be my fraternity. She was, by any account, a stranger in a strange land. She was also, on different days and on different occasions, a pioneer, a firebrand, a free spirit, a rebel, a confused girl, a vigorous opponent of the war in Vietnam, the bruised daughter of alcoholics, not to mention a shitbird – the name given to pledges at Heorot between their committing to the fraternity and sink night – the throwback ritual weeks later, when they were made official members.

Her experience at Dartmouth was a journey almost as tumultuous as ours – at least those of us who drew a bad draft number that December 1st. It seems particularly fitting that the Dartmouth motto – VOX CLAMANTIS IN DESERTO (“A voice crying in the wilderness”) – should have resonated so profoundly with those of us trying to find our own voices in a landscape of so much noise. Finding one’s voice is a natural quest, and college years, for many reasons, are often a time when we try out many voices before finding our own. But life and death decisions by dint of a national draft lottery added a degree of difficulty unique to our class. Perhaps the cooking analogy is boiling potatoes in an open pot, versus a closed-lid pressure cooker. Our spuds were boiled top on, and the hissing and whistling we heard was our own, shrill voices – some trying out, others crying out for a voice that fit.

We were a band of brothers and a confederacy of dunces all rolled into one. As I have compressed two years into one, I have also, in places, blended several characters into one, and given most new names – not only to protect those who have left the great stage and might want some earlier performances to go unreviewed – but also to keep the options open for anyone contemplating a late-life run for political office.

Parkhurst Takeover – Spring 1970

Dramatic license has been taken, but almost everything you will read happened – either experienced by me, or told to me. I placed the takeover of the Parkhurst Administration building in our senior year because it represented the most dramatic anti-war event of those undergraduate days. It also symbolized the Vietnam angst our class felt as we faced an unsheltered future newly burdened with draft numbers. Similarly, the “Magnificent Seven” (a junior year phenomenon) got relocated because their own journey seemed a match for the chaotic, all-male misadventures one year later. Both components are presented as they were (at least to my eyes); only the time frame has been altered. All of which makes this story something of a hybrid – part memoir, part account – non-fiction, strategically massaged. My goal is to create a collegiate chorus reflective of the campus collective in that cacophonous time. The inclusion of photographs is intended to complement that portrait – to put a few faces to a time and a place that gestated in me for so many years.

I do know this: if college experience was ever a high stakes poker game (as ours, through the draft lottery, turned out to be), and someone from another era pushed their recollections into the center of the table, all in, I’d be confident in saying: “I’ll see your college years… and raise you 1969-1970.”